Retrofit Financing

Download documents

Read on this page

Deep Building Retrofit Funding and Financing series

Our Deep Building Retrofit Funding and Financing series is designed to grow knowledge and capacity around financial tools and strategies for deep building retrofits for commercial, institutional, and multi-unit residential buildings. Part one of the series, Funding and Financing 101, features presenter Rochelle Owen, an expert with 35 years of experience in green energy projects in the built environment. This webinar also features Judy Wall, President of East Port Properties, discussing strategies for deep retrofit funding and financing. You can watch the webinar here, and also access the pdf of the presentation slides.

Part 1: Funding and Financing 101

Our Deep Building Retrofit Funding and Financing series continues with part two, Building The Business Case 101. This webinar provides detailed strategies on developing a compelling business case for deep retrofits using data, visuals, and storytelling. Presented by Rochelle Owen, this webinar also features Heather McGeown, Executive Director of BOMA NS. Heather brings an extensive background in private development coupled with knowledge of effective business cases. You can watch the webinar here, and also access the pdf of the presentation slides.

Part 2: Building The Business Case 101

Deep Building Retrofits: Funding & Financing Guide

Version: FALL 2025

This is the second version of this guide, and we value your feedback so we can continue to improve it. Please take this short survey or email drai@hci3.ca with comments.

Acknowledgements

HCi3 would like to thank Rochelle Owen of Rochelle Owen Consulting as the lead author and senior advisor on this guide. We also acknowledge our partnership with The ReCover Initiative, who is leading the regional Deep Retrofit Accelerator that encompasses our work on financing retrofits. This program is funded in large part by Natural Resources Canada, with additional support from Echo Foundation, McConnell Foundation, the Trottier Family Foundation and HCi3.

Disclaimer: There are hundreds of funding and financing programs. We have focussed on those that have some connection to deep building retrofits. We recognize funding programs are continually opening and closing, and we aim to be current as of the date of publishing this guide. We have listed programs that are still active, although the application window may be currently closed; however, groups can plan for future funding rounds.

Introduction

This funding and financing resource guide has been developed by the Halifax Climate Investment, Innovation and Impact Fund (HCi3) as a support to building owners, managers, consultants and other professionals seeking to advance deep building retrofits. HCi3 is a partner on the Atlantic Canada Deep Retrofit Accelerator led by the ReCover Initiative that seeks to accelerate the pace of deep retrofits in our region. This guide is primarily intended for private, non-profit, municipal, and provincially owned commercial, institutional and multi-unit residential buildings, as well as any building stock owned by Indigenous communities in Atlantic Canada.

What are Deep Building Retrofits?

The term “deep building retrofit” commonly applies to projects where buildings undergo significant upgrades to address deferred maintenance, functionality, comfort, energy efficiency and pollution reduction (e.g. reduction in greenhouse gases (GHG) and criteria air contaminants). Deep retrofit strategies are implemented in phased approaches timed with facilities renewal and/or as a major project. Core strategies used to achieve deep building retrofits often include:

Building envelope upgrades: wall, roof, and floor insulation; new windows and doors;

Lighting and electrical systems changes: efficient lighting and controls, daylighting optimization, peak and back up storage and management, and external shading;

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) enhancements: Mechanical ventilation heat recovery (MVHR); new efficient ventilation system; new heating/cooling supply and distribution including possible connection to district energy, building energy and automation management (BEM), new heat supply (radiators, floor systems); air and ground source heat pumps; and

Renewable energy systems and additions (e.g., solar photovoltaic).

Key questions to reflect on as you read this document:

Do we have a funding and financing approach (Table 1)?

Have we explored all funding and financing sources for our project (Figure 1 & Table 2)?

Can we use organizational budgets differently to finance projects (Figure 2)?

Are we aware of current grant, loan, rebate, and subsidy programs (Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)?

Is there merit, the interest or ability in creating a separate structure like a special purpose vehicle (SPV), green bond, or development corporation?

Have we tapped into existing resources, networks, and services?

1. What is our project funding and financing strategy?

Before you begin to identify funding and financing sources, it can be helpful to think through a strategy. A strategy may have elements to consider such as matching mutual objectives, leveraging and stacking funds, timing, and partnerships (Table 1).

Table 1. Funding and Financing Strategy Considerations

| Project Objectives | Often funders will not have enough funding for all applications. If projects can be used as a template for others, provide new ideas for solving a problem or addresses other social and environmental challenges, then the project may have broader appeal. Linking your program objectives to the core mandate of the fund is essential. Some questions to consider: What is unique about the project? Is the project innovative? How does it meet the grant fund or financing program objectives? Is it scalable to serve as a template for others? Does it address other societal, environmental, and safety objectives? What type of community services will the building provide? Should our project objectives be updated to reflect these considerations? Do we have leadership approval to apply for grants? Do we have solid cost estimates? |

|---|---|

| Stacking & Leveraging | The financial business case for a deep retrofit may include stacking and leveraging various types of cash, debt, and/or equity. What type and amount of funds is our organization putting towards the project (consult Figure 2), e.g., facilities renewal and utility savings? How can we leverage our funds with external grants and financing (Tables 3-7)? Most grants will require in-kind and cash contributions. How can we stack more than one grant together? Can we take on debt? If so, for how long at what interest rate? In general, there may be a percentage limit of how much federal grant or provincial government funding you can stack, though you may be able to stack a higher percentage with a mix of federal, provincial and owner contribution. |

| Timing | Grant programs may operate for the long or short term. Some may be available for many years and some for a couple of years. Most grant funds require a competitive application. There is often a window of time to apply. Preparing ahead with a funding strategy allows for deeper engagement with funders and time to prepare funding application information. Do we have program contact information, and have we made connections with program representatives prior to applying? Have we signed up to program communications offerings if available (e.g., newsletter)? |

| Partnerships | Partnerships with other public and private sector organizations can provide co-benefits such as financing and meeting additional community goals, though they can add new administrative, risk and governance considerations. |

2. What types of funding and financing sources are there?

Embarking on a deep building retrofit can open new funding and financing sources beyond standard facilities capital, renewal, and operating budgets. In many cases, core contributions from facilities funding are leveraged to unlock new funding or strategies to meet multiple building objectives (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1. Funding and Financing Sources

Table 2. Funding and Financing Sources including deep retrofit examples

| Source | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Financial Reserves | Accumulation of non-allocated funds. Provides security to manage unknown risks and take advantage of a strategic opportunity. A deep building retrofit project may unlock additional grant funding that creates a positive business case with a one-time infusion from financial reserves or a strategic initiative fund. |

| 2. User Fees, Fines, and Fares | Organizations charge fees, fines and fares for products, programs, and services. A percentage of fees, fines, and fares can be used to fund climate and energy projects. A common example is a percentage of parking fees is used to fund transportation demand management programs and infrastructure such as building bike racks or electric vehicle chargers. A cap-and-trade type program can be used by governments to collect fines and reallocate them to programming. |

| 3. Tax Revenue | Money collected from government is used for public spending. Common taxes include income, property, sales, and corporate. Some municipal governments are adding a climate levy on property taxes to raise funding for climate actions, including deep building retrofits. Governments have used performance regulations as well as other policy levers to raise funding. |

| 4. Liquidating Assets | Selling off items such as property, investments, and products to generate cash or pay debt. Some organizations sell assets to help fund major renovations of core buildings. |

| 5. Grants and Contributions | Grants provide non-repayable financial assistance. Grants can be project specific or core funding (set amount annually for an agreed upon period.) Grants are provided by governments, foundations, non-profits, and businesses. Contributions can include time, staff support, or money for a specific expense or product. There are specific grants and contribution programs for deep building retrofit projects (Tables 3,4,5,7) including provision of staff (e.g., embedded energy manager or Climate Help Desk services) and financial assistance for core technology deployment and studies. There also may be grants specific to upgrading the functionality of a particular building type (Table 6). For example, if the building is a museum, there may be energy and climate grants plus specific grants for upgrading museum buildings spaces, systems, and accessibility. |

| 6. Subsidies and Rebates | A subsidy is a payment or avoided payment made to influence production or prices. Examples include tax credits, subsidized loans, or a guaranteed price. A rebate is a financial incentive in the form of a refund or discount such as a flat fee discount per product. Deep retrofit product rebates are provided by government and non-profits. The federal government launched the Clean Economy Investment Tax Credit for businesses to support clean technology like renewable energy for buildings. Subsidized loan products are also available for building retrofit projects facilitated through the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) and related partners. Feed-in Tariff and Community Economic Development Investment Fund (CEDIF) programs have been used by government to support the development of community-based renewable electricity projects. |

| 7. Donations | A donation is a gift from an individual, corporation or foundation. A gift can be cash, services, eligible securities, or goods. Registered municipalities, non-profits, universities and colleges, and businesses can all receive donations. Building-specific donations can focus on green features such as renewable energy systems. |

| 8. Loans/Bonds | A loan is money borrowed from a lender with the agreement to pay back the amount, usually plus interest, within a specific period. Occasionally, there are government programs that support a 0% interest loan. There are a wide variety of loans, including bank and government loans, lines of credit, and mortgages. A bond is an investment vehicle that represents a loan to a borrower by an investor. Traditional loans are used for building retrofits along with specialized products including Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) programs, and preferential loans provided through groups like CIB and SOFIAC. Some governments (including municipalities), companies, and universities have created their own green bonds to finance climate infrastructure projects. |

| 9. Vendor Financing | A company provides financing to a customer to purchase their products. Energy service companies (ESCOs) provide financing for a deep energy building retrofit project that the owner can pay back over a set period using utility savings. A company may lease building related equipment like a heat pump to be paid back over a set time. |

| 10. Equity | A company can raise money selling shares in their company. Some public companies can raise funding for deep retrofit projects through this mechanism. Venture capital funds like the Canada Growth Fund provide equity financing for projects reducing emissions. |

How can we use funding and financing sources strategically?

An organization can use both sides of the budget sheet to efficiently integrate internal assets, create new structures, and use different management approaches (Figure 2). For example, instead of owning an asset, it could be rented or leased. Solar companies have financed solar installations for buildings where the owner rents the roof space or rents to own the system. Utility budgets can supplement facilities renewal, operating and capital budgets and can be used to pay down external and internal loans through mechanisms like green revolving funds, power purchase agreements, or energy performance contracts. Existing staff and new staff can be deployed to new roles in the organization focusing on sustainability, green building, energy performance contracting, and commissioning.

Figure 2. Using Both Sides of the Budget Sheet for Deep Building Retrofit Business Cases

Who provides funding and financing?

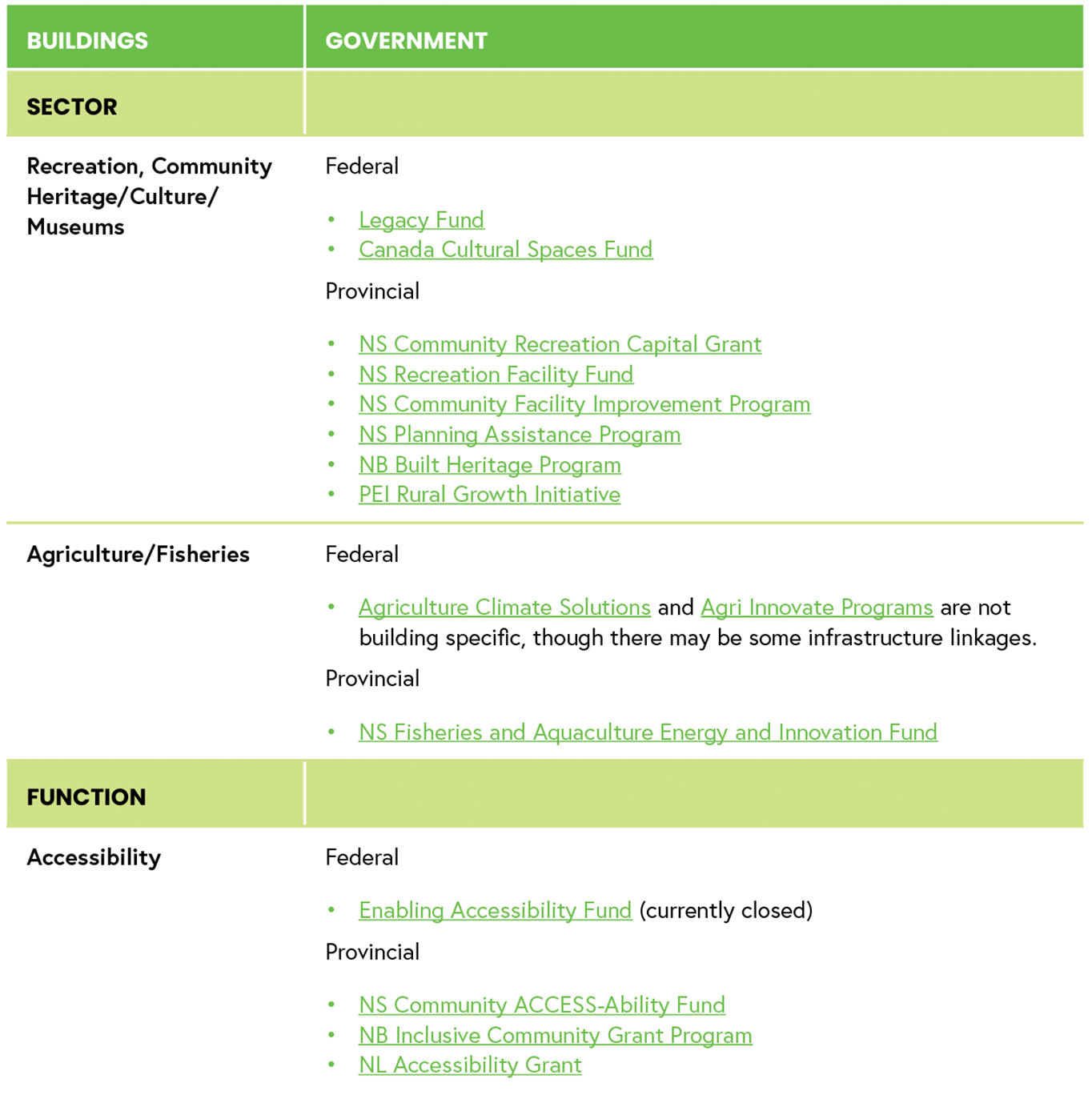

Understanding which government department or agencies (federal/provincial), foundations and private organizations support broad climate, energy and sustainability actions, including building retrofits is an important first step. Building function (e.g., a museum or farmers’ market) may open additional sector specific funding. Other government grants and private loans may be available for broad improvements (e.g., accessible entrances and washrooms) (Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

Eligible programs are opening and closing all the time. Invariably, any list of programs such as this comes with a cautionary note that it may not be completely up-to-date given ongoing changes. In the tables below, we aim to provide the main funding page for the organization followed by a grant name. If the grant is closed, the reader can navigate back to the main page and review programs. Not all building owners are eligible for all grants, donor programs, loans, rebates, or tax incentives. A good tip is to connect with program contacts as they and other fund navigators can help answer questions about applicability and eligibility.

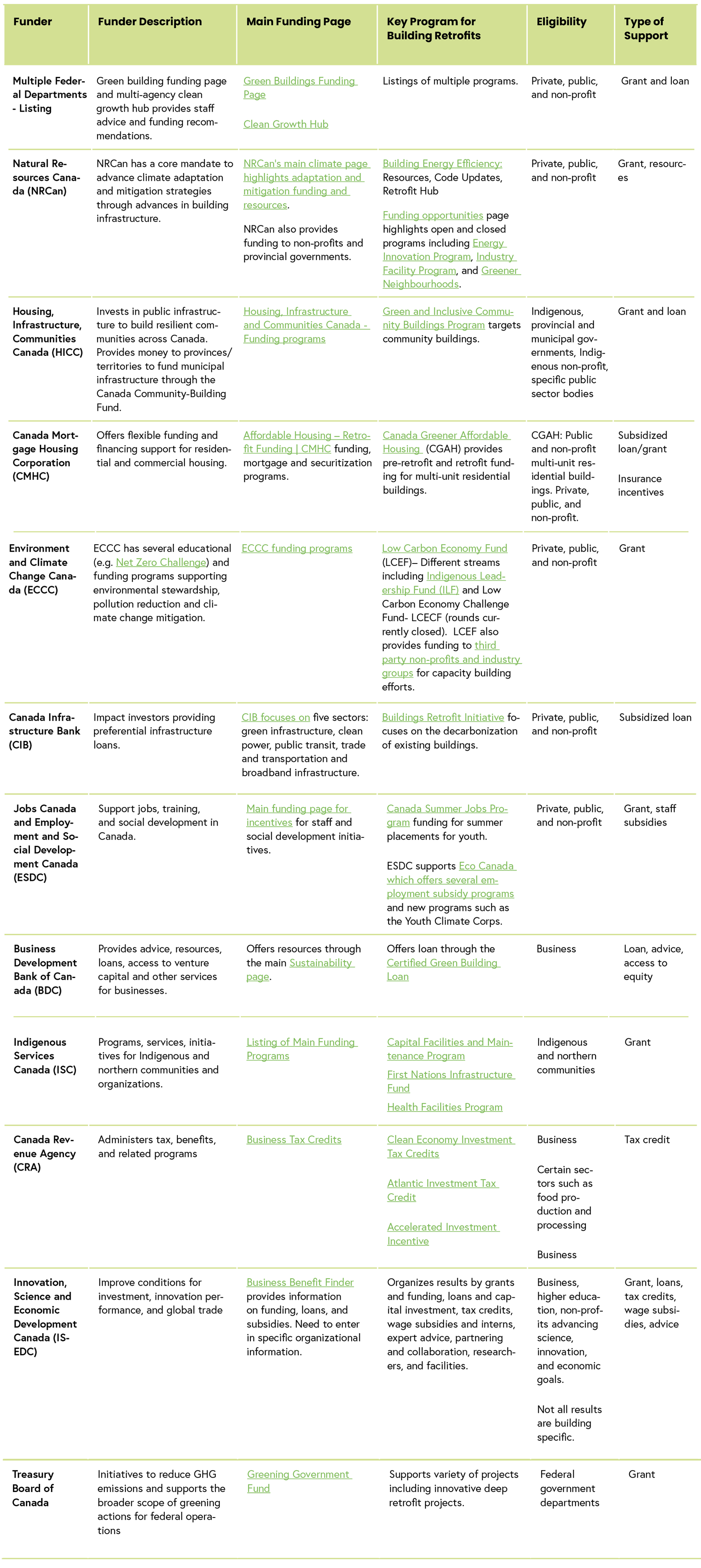

Federal Government

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC), and Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) are the core federal bodies focused on climate action and building retrofits. Other departments and agencies may have sector specific programs or identify building energy retrofits as a method to achieve other departmental goals, such as economic development or housing. These may include, but are not limited to, Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA), Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB), Canada Mortgage Housing Corporation (CMHC), Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISEDC) (Tables 3, 5).

Provincial Government

The four Atlantic Provinces have several departments and agencies including natural resources and energy, environment and climate change, and housing and infrastructure similar to the federal government and in some cases, government-led efficiency organizations (Table 4). Sector specific building funding is found through economic development agencies and sector focussed departments (e.g., building upgrades for farms through agriculture) (Table 4).

Non-Profit and Foundations

Non-profit organizations (including charitable organizations and cooperatives) raise funding from individuals, government, foundations, and other revenue generating activities. Some national, regional, and provincial non-profits provide services such as staff support, technical services, resources and, in some cases, funding for building energy retrofits (Table 6).

Foundations are non-profit or charitable trusts that provide grants and, in some cases, subsidized loans for charitable purposes. Canadian-based and international foundations have funded in the region. Foundations may have open application calls or prefer to select partners they would like to work with. Philanthropic Foundations of Canada lists major foundations in Canada. Some foundations have created the Environment Funders of Canada and the Clean Economy Fund to support work in this area.

Private Sector

Private sector funding for deep building retrofits comes largely in the form of debt and equity financing, though some private sector organizations provide rebate and discount programs. Some private sector groups, such as banks, also have defined giving programs supporting charitable work. The focus of these charitable contributions is often broad and may not have direct links to building retrofits, though some projects may qualify, and often require a focused conversation with a program representative.

Factors including the sector that the building owner belongs to, their credit rating, the project risks, and an organization’s size will determine their access to private funding. Building owners are looking for the most favourable interest rate and suitable term lengths. Private lenders are looking for credit-worthy owners with low-risk projects. Private debt financing instruments include:

Traditional loans (banks): Products include business term loans, equipment loans, lines of credit, and mortgages. Rates are dependent on the project and client. Banks are adding specific product offerings and resources for environment and climate action including deep retrofits and have charitable programs that may or may not match with project objectives (Table 7).

Point-of-sale loans, lease-to-own, or rental equipment options are provided by suppliers/installers sometimes in conjunction with financing groups. Product suppliers work through distributors or on their own to sell directly to the owner, the owner’s team or through an installer.

Utility on-bill financing and rebates are provided by utility companies to their customers as an easy way for customers to access upgrades like heat pumps, electric thermal storage units, and solar panels, to be paid on their utility bill.

Energy Performance Contracts (EPC): EPCs have been around for several years. Organizations like the federal government have created a standing offer with energy service companies (ESCOs) to provide energy performance contracts. With EPC contracting, the ESCO can cover the costs for upfront studies that can be rolled into the project costs if the project goes ahead. If not, the owner will pay for the studies at that time. The ESCO also offers private financing (which they receive from private investors) so the owner does not have to use their capital, and they can pay it back with energy savings and other budget sources. Some owners do not take the ESCOs private financing because they can secure financing at a lower rate. Organizations like SOFIAC use an energy savings performance contracting model where building owners can pay back project costs, with no upfront capital, through utility savings and facilities renewal budgets.

Energy-as-a-Service (EaaS): Can often be a subscription-based monthly service fee for devices and equipment or management of energy (e.g., manipulating building automation control sequencing). The owner does not pay for the product but may pay subscription fees. Groups like Efficiency Capital are promoting some of their services as energy-as-a-service. This model is also being used for solar panel installations in some countries. These organizations generally have a minimum project size that varies by company.

Table 3. Federal government funders

(To access the links in the above image, please download the document in PDF form at the top of the page)

Table 4: Provincial funders that fund building retrofits within municipalities

Table 5. Potential sector or function-specific building funding

Table 6: Non-Profit funders that fund building retrofits within municipalities

Table 7: Financial Sector Programs and Resources

Resources and Networks

HCi3 Primers: HCI3 has developed two primers on Making the Business Case and Alternative Financing Strategies. Each Primer provides a summary of the topic and a curated list of existing resources.

Fund and Program Navigators: Private and public programs will have staff dedicated to promoting offerings. Connecting with staff provides up-to-date information. Some government entities have specific fund navigator roles including the:

Nova Scotia Federation of Municipalities Fund Navigator, Lucy MacLeod, fundnavigator@nsfm.ca, 902-717-9761. Specific grant funding page dedicated to Retrofits and New Builds for municipalities that has a list of programs found in this guide and may have new ones depending on the frequency of updates.

Nova Scotia Climate Funding Navigator: ClimateFundingNavigator@novascotia.ca.

Networks, Conferences, Training, and Resources

There are free and paid professional development opportunities and resources offered through a variety of organizations from non-profits, government, associations, private sector, and continuing education. For deep building retrofits, here is a selection of organizations that offer training, resources, networking opportunities and conferences.

Resources for Building a Business Case for Deep Retrofits

Version: SPRING 2025

Disclaimer: This is the first version of the primer and may be missing information. We value your feedback. Please email drai@hci3.ca with comments or suggestions for additional resources.

Introduction

To make a business case, a project sponsor must deliver a package of compelling information to senior decision-makers requesting to spend resources for a desired result – in this case, a deep building retrofit. Depending on your organization, there may be a set template used. Key components of the business case will often include:

Setting the Context: background, issue, community and organizational engagement, and project scope.

Identifying the Value: value proposition, project benefits, organizational alignment.

Options Analysis: Identifying and evaluating options, including the status quo.

Risk Assessment: Identifying and assessing risks and providing mitigation strategies.

Financial Assessment: For a building project, this may include a project proforma. A proforma may list project costs (capital, operation, renewal/disposal) and revenues (utility savings, facilities renewal, grants), outline cashflow, and provide a sensitivity analysis. Project financials are compared to the status quo using financial metrics such as internal rate of return (IRR), return on investment (ROI), net present value (NPV), and payback period (PP).

Recommendations

Resources

The following resources are from existing public organizations. Please email us if you have a good resource that you think should be highlighted. Resources are listed in alphabetical order by the author, date (when available), and title, which is hyperlinked. A short description provided by the author is also included. Resources were selected that are relevant to making the business case for deep building retrofits.

Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC). Buildings Retrofit Savings Calculator. Use the calculator to estimate your long-term savings in energy costs, payback period and the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Canada Green Building Council (2019). Making the Case for Zero Carbon Buildings. The report makes a strong business case for making every new building zero-carbon.

Canadian Federation of Municipalities - Green Municipal Fund. Developing a Business Case for an Energy-Efficiency Retrofit. This factsheet for housing providers explains the requirements for a business case, including its purpose and how you can develop one for an energy-efficiency retrofit.

Rocky Mountain Institute (2012). Guide to Building the Case for Deep Energy Retrofits. This guide provides a framework for preliminary considerations in the value of deep energy retrofits for commercial buildings, and it offers guidance on how to conduct further analysis.

Toronto Atmospheric Fund (2020). The Case for Deep Retrofits. This report reviews the business case and financing options for deep retrofits in the multi-unit residential building sector and makes recommendations for improving business case evaluation and financial supports.

Treasury Board of Canada (2009). Business Case Guide. The purpose of this document is to support the development of a strong business case that links investments with program results and, ultimately, with the strategic outcomes of the organization.

UK Green Building Council (2024). Building the Case for Net Zero: Retrofitting Office Buildings. This report focuses on deepening understanding of how to retrofit large (>1,000 m2) commercial office buildings towards net zero, the retrofit measures required, potential impacts, and associated costs.

US Department of Energy (2016) Making the Business Case for Energy Efficiency in Commercial Buildings. This toolkit includes a selection of resources to support commercial building operational staff in making the business case for the implementation of energy efficiency projects to their upper management.

Alternative Financing for Deep Building Retrofits: A Primer

Version: SPRING 2025

Disclaimer: This document is a first draft and we value your feedback to improve future versions. Please email drai@hci3.ca with comments.

Introduction

To finance deep building retrofits, building owners commonly use internal resources, such as facilities renewal budgets, external debt through commercial loans, and grants, if available. In addition to these strategies, building owners can use other alternative mechanisms to leverage internal and external resources for building retrofits. This primer aims to provide a brief overview of these mechanisms along with resources that provide more in depth information.

Alternative Financing Strategies

Alternative mechanisms for financing building retrofits include:

Energy performance contracting (EPC): An energy service company (ESCO) designs, builds, and can secure financing to improve energy management in a building or buildings. A performance guarantee is provided, and utility savings are often used to pay back the cost of the project.

Energy purchase agreements:

Energy-as-a-Service (EaaS): EaaS can often be a subscription-based monthly service fee for devices and equipment or management of energy. The owner does not pay for the product but may pay subscription fees.

Energy Purchase Agreements (or power purchase agreements (PPAs)) are contractual agreements between electricity or heat generators and buyers. They are commonly used in the renewable energy industry for the owner’s purchase of solar and wind electricity.

Green bonds: Green bonds are debt issued by public and private organizations to finance climate and environmental projects.

Green leasing: Green leasing is a lease or rental agreement that outlines how tenants and landlords share in the energy savings benefits of a deep building retrofit.

Green revolving funds (GRF): GRFs are internal funding mechanisms to help finance sustainability and energy projects. GRFs may be seeded with an initial contribution. Project savings are then used to pay back the fund. A variation of a GRF is an uncapped funding mechanism where project savings are used to pay down projects and the capital is not limited to a GRF fund amount.

Internal carbon fees: Monetary value is placed on an organization’s greenhouse gas emissions. This value can be invested in climate projects and programs.

On-bill financing: On-bill financing and rebates are provided by companies to their customers as an easy way for customers to access upgrades like heat pumps, electric thermal storage units, and solar panels, to be paid on their utility bill.

On-bill financing (OBF) is where the utility is the lender. Ratepayer funds are the most common funding source.

On-bill recovery (OBR) is where the capital provider is a third party (lender or government), and the utility operates as a repayment conduit. A utility may opt to use its own funds to offer administrative support or credit enhancements.

Tariff On-bill (TOB) is where building retrofits are not considered a loan, unlike OBR and OBF programs. Instead, they are structured as a cost recovery charge tied to the utility meter where upgrades are made and the charge on the bill is treated as equal to other utility charges.

Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE): PACE programs exist for the commercial sector, in addition to the residential sector. A municipality adds an assessment or charge to a commercial property owner’s property tax bill (or another local improvement charge) for a period (e.g., 10 years) to pay back an energy efficiency loan to the property owner. Funding can come from the municipality or other funding sources. Enabling legislation is required.

Credit Enhancements can help reduce a financial institution’s perceived risk. Organizations use credit enhancements to motivate and/or negotiate with third-party financial institutions for more favourable loan products. This could include broadening consumer access to financing (e.g., lending to borrowers that they may not have otherwise considered, relaxing underwriting criteria), extending loan terms, lowering interest rates and/or offering repayment flexibility. Loan loss reserves (LLRs) are a common types of credit enhancement. Under an LLR, public funds are set aside (or reserved) as loans are issued (e.g., typically 5% of the total loan portfolio) to cover the financial partner's losses (or a portion of those losses), should they occur. Credit enhancements could also include interest rate buy downs and mortgage loan insurance (e.g., MLI Select)

Resources

The following resources are from public and private organizations. Please email us if you have a good resource that you think should be highlighted. Resources are listed in alphabetical order by the author, date (when available), and title, which is hyperlinked. A short description provided by the author is also included. Resources were selected for their focus on alternative funding and financing strategies for deep building retrofits.

City of Toronto (2025). Green Debenture (Bond) Program. The City’s Green Debenture Program leverages the City’s low cost of borrowing to finance capital projects that contribute to environmental sustainability.

Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference (2016). Financing Energy Efficiency Retrofits in the Built Environment. This study examined different innovative financing mechanisms used to promote energy efficiency upgrades in the housing and building sectors with a focus on various initiatives in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. Best practices were identified for models that align savings with the cost of loan repayments through repayment on utility bills or property tax bills, as well as traditional credit sources from financial institutions, other suppliers and governments and their agents.

Green Finance Institute (2025). Local Climate Bonds. Local climate bonds (LCBs), also known as community municipal investments (CMIs), are an innovative green finance mechanism that enable local authorities to raise citizen and institutional borrowing to fund environmental and social impact projects.

Green Lease Leaders (2025). Reference Guides for Tenants and Landlords. The landlord and tenant reference guides offer recommendations for building owners looking to implement green leasing practices across their portfolios.

KPMG (2023). How to Get Internal Carbon Pricing Right. This paper outlines how internal carbon pricing works and how to go about adopting it.

Institute for Market Transformation. Energy Savings Agreements. An energy service agreement is a pay-for-performance, off-balance sheet financing solution that allows customers to implement energy efficiency projects with zero upfront capital expenditure.

Leventis et al. (2016). Current Practices in Efficiency Financing: An Overview for State and Local Governments. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. This report distinguishes between “traditional” financing products (e.g., loans and leases) that are commonly used to pay for energy efficiency as well as many other goods and services, and “specialized” products (e.g., PACE and on-bill financing products) that are specifically designed to support energy efficiency and other clean energy installations and to overcome market barriers.

Natural Resources Canada (2022). Energy Performance Contracting (EPC). Find out more about EPCs by downloading this step-by-step guide.

Second Nature (2025). Revolving Funds. Revolving funds are internal investment vehicles that provide funding to internal parties for implementing sustainability projects that generate cost savings.

US Department of Energy (2025). Financing Navigator Resources. Each building sector faces different challenges and opportunities regarding financing for energy efficiency and renewable energy projects. The sector-specific financing primers provide a summary of how energy financing is done within each sector.

US Department of Energy (2016). Green Revolving Funds Tool Kit. A green revolving fund (GRF) is an internal capital pool that is dedicated to funding energy efficiency, renewable energy, and/or sustainability projects that generate cost savings.